How do you calculate the derivative of a function from the definition?

The definition of the derivative of a function f (x) at a point x = a was given in Section 11.3,

$$f’\left( a \right) = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{f(a + h) – f(a)}}{h}$$

provided this limit exists. We can adapt this definition to find the derivative of a function by changing the constant a to a variable x.

provided the limit exists. The symbols f ′(x), are read “f prime of x”.

We can apply this definition in a manner similar to how we applied the definition of derivative of a function at a point.

To find the derivative of f (x) or f ′(x),

- Evaluate the function f (x) at x + h to give f (x + h). Simplify this expression as much as possible.

- Form and simplify the difference quotient $\frac{{f(x + h) – f(x)}}{h}$.

- Take the limit as h approaches 0 of the simplified difference quotient.

Let’s use this strategy to find the derivatives of several functions.

Example 2 Find the Derivative

Use the definition of the derivative to find the derivative of the function $$f(x) = 2x – 7$$

Solution To apply the definition of the derivative to this function, we must evaluate f (x + h). Replace x in the function with x + h to yield $$\displaylines{

f(x + h) = 2\left( {x + h} \right) – 7 \cr

= 2x + 2h – 7 \cr} $$

It is important to note that we are replacing x with the group x + h in parentheses. Now form the difference quotient,$$\frac{{f(x + h) – f(x)}}{h} = \frac{{\left( {2x + 2h – 7} \right) – \left( {2x – 7} \right)}}{h}$$

To make the limit easy to evaluate, let’s simplify the difference quotient as much as possible.

$$

\begin{align*}

\frac{{f(x + h) – f(x)}}{h} &= \frac{{\left( {2x + 2h – 7} \right) – \left( {2x – 7} \right)}}{h} && {\color{red}{\small \text{Remove the parentheses and subtract each term}}} \cr

&= \frac{{2x + 2h – 7 \color{red}{- 2x + 7}}}{h} && \cr

&= \frac{{2 \color{red}{h}}}{\color{red}{h}} && {\color{red}{\small \text{Combine like terms}}} \cr

&= 2 && {\color{red}{\small \text{Reduce the quotient}}} \cr

\end{align*} $$

Substitute this expression into the definition of the derivative:

$$\begin{align*}

f'(x) &= \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{f(x + h) – f(x)}}{h} \cr

&= \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} 2 \cr

&= 2 \cr \end{align*}$$

The derivative of the linear function $f(x) = 2x – 7$ is $f'(x) = 2$.

Example 3 Find the Derivative

Use the definition of the derivative to find the derivative of the function$$g(t) = {t^2} + 3t + 7$$

Solution In this example, we’ll follow the same strategy for finding the derivative. However, since the name of the function is g(t), we need to adjust the definition of the derivative to read$$g'(t) = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{g(t + h) – g(t)}}{h}$$

Substitute t + h for t in g(t) to give

$$

\begin{align*}

g(t + h) &= {\left( {t + h} \right)^2} + 3\left( {t + h} \right) + 7 && \cr

&= {t^2} + 2ht + {h^{^2}} + 3\left( {t + h} \right) + 7 && \color{red}{\small \text{Multiply }} \color{red}{\left( {t+h} \right)\left( {t+h} \right)} \cr

&= {t^2} + 2ht + {h^2} + 3t + 3h + 7 && \color{red}{\small \text{Multiply 3 times }} \color{red}{t+h} \cr

\end{align*}

$$

If we place this expression and the expression for into the numerator of the difference quotient, we get

$$\begin{align*}

\frac{{g(t + h) – g(t)}}{h} &= \frac{{\left( {{t^2} + 2ht + {h^2} + 3t + 3h + 7} \right) – \left( {{t^2} + 3t + 7} \right)}}{h} && \color{red}{\small \text{Subtract and simplify}} \cr

&= \frac{{{t^2} + 2ht + {h^2} + 3t + 3h + 7 \color{red}{- {t^2} – 3t – 7}}}{h} && \color{red}{\small \text{Combine like terms}} \cr

&= \frac{{2ht + {h^2} + 3h}}{h} && \cr

&= \frac{{\color{red}{h}\left( {2t + h + 3} \right)}}{\color{red}{h}} && \color{red}{{\small \text{Factor }}h{\text{ and reduce}}} \cr

&= 2t + h + 3 && \cr

\end{align*}

$$

With this expression in the definition of the derivative, we write

$$

\begin{align*}

g'(t) &= \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{g(t + h) – g(t)}}{h} \cr

&= \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \left( {2t + h + 3} \right) \cr

&= 2t + 3 \cr

\end{align*}

$$

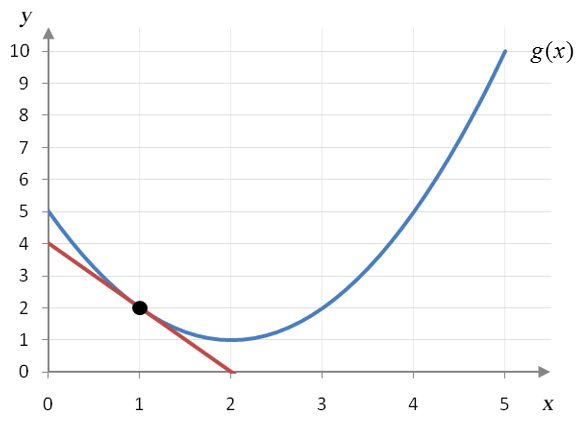

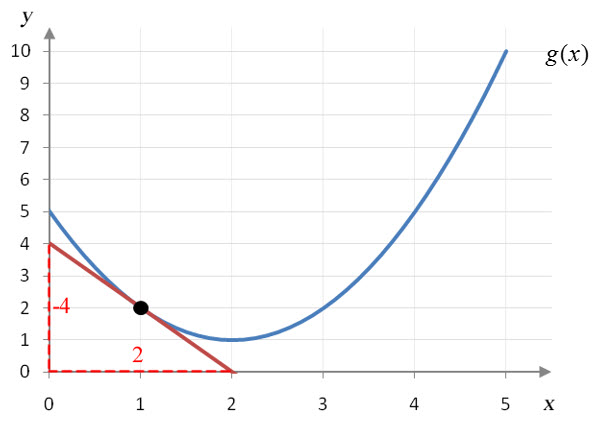

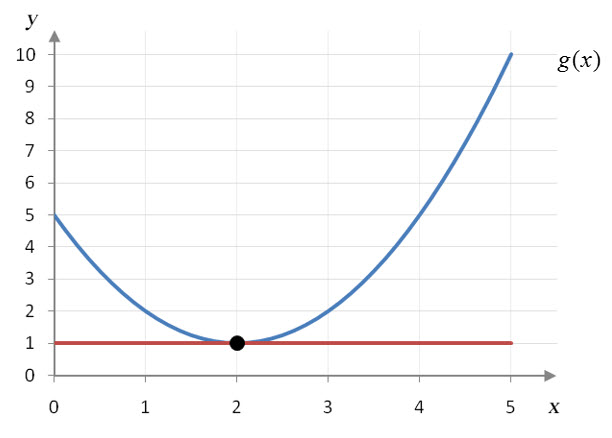

The derivative of the quadratic function $g(t) = {t^2} + 3t + 7$ is the linear function $g'(t) = 2t + 3$.

Example 4 Find the Derivative

Use the definition of the derivative to find the derivative of the function$$j(t) = {e^t}$$

Solution The definition of the derivative for this function is$$j'(t) = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{j(t + h) – j(t)}}{h}$$

Using the exponential function, the difference quotient is$$\frac{{j(t + h) – j(t)}}{h} = \frac{{{e^{t + h}} – {e^t}}}{h}$$

This expression can be simplified, but not as easily as Example 2 or Example 3.

In this case we rewrite ${e^{t + h}}$ as ${e^t}\;{e^h}$. By doing this, we can factor the numerator:

$$

\begin{align*}

\frac{{j(t + h) – j(t)}}{h} &= \frac{{{e^{t + h}} – {e^t}}}{h} \cr

&= \frac{{{e^t}\;{e^h} – {e^t}}}{h} \cr

&= \frac{{{e^t}\left( {{e^h} – 1} \right)}}{h} \cr

\end{align*}

$$

From this simplified difference quotient, we can write out the definition of the derivative,

$$

\begin{align*}

j'(t) &= \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{j(t + h) – j(t)}}{h} \cr

&= \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{{e^t}\left( {{e^h} – 1} \right)}}{h} \cr

&= {e^t} \cdot \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{{e^h} – 1}}{h} \cr

\end{align*}

$$

The factor ${e^t}$ is a constant with respect to h, so it can be moved outside the limit. To complete the derivative, we must evaluate the limit.

For this limit we’ll find the limit by creating a table of values for for smaller and smaller h values.

| h | $\frac{{{e^h} – 1}}{h}$ |

| 0.1 | 1.051709181 |

| 0.01 | 1.005016708 |

| 0.001 | 1.000500167 |

| 0.0001 | 1.000050002 |

| 0.00001 | 1.000005000 |

The table suggests that as x gets smaller and smaller, the value of the quotient approaches 1 or $$\mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{{e^h} – 1}}{h} = 1$$

Using $\mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{{e^h} – 1}}{h} = 1$ in the expression for the definition of the derivative yields

$$

\begin{align*}

j'(t) &= {e^t} \cdot \mathop {\lim }\limits_{h\,\, \to 0} \frac{{{e^h} – 1}}{h} \cr

&= {e^t} \cdot 1 \cr

&= {e^t} \cr

\end{align*}

$$

The derivative of $j(t) = {e^t}$ is $j'(t) = {e^t}$.